Why I believe that us engineers should carry a techno optimist attitude

Us engineers must trust that our work can make the world better

On social media, I encounter a massive amount of skepticism about the ability of Engineering to help solve the big problems in the world. Plenty of professors appear to focus on the downsides of technology. AI-risk, de-growth, TESCREAL, you name it. While these voices are loud, they neither reflect how engineers usually think nor, do they (in my opinion) represent how we engineers should think. If our life’s work is about improving the worldby engineering, we can only truly live our agency if we assume that we can improve the world through better engineering1.

Pessimism has negative consequences

A climate of excessive pessimism produces bad decisions. A powerful example of this is Germany’s anti-nuclear movement. In the wake of environmental concerns, Germany made the decision to phase out nuclear power, shutting down plants that provided low-carbon energy. This well-intentioned move led to an increased reliance on coal, paradoxically worsening carbon emissions and slowing progress toward cleaner energy solutions. This example highlights how even well-intentioned environmental advocacy can sometimes lead to unintended consequences when technological solutions are prematurely dismissed. When critique turns into outright rejection of technological solutions, we risk making the world worse, not better.

The criticism should be seen as a design problem, not a barrier

There are problems with today’s engineered system (thank god as I otherwise would rightfully lose my job). From the rightful critique that technology can reinforce existing power imbalances to the alarm over capitalism’s exploitative tendencies or the contention that degrowth might be our only escape, these are all legitimate warnings that underscore one truth: our political, social, and economic systems themselves demand the creative rigor of engineers. Technology is never neutral, but that is precisely why we can—and must (depending on what we jointly see as our goals) —engineer better frameworks for distributing wealth, regulating industries, reshaping energy policies, and amplifying a wide range of voices. Just as we refine a machine design to address weaknesses, we can embed well-being and sustainability into policies, market structures, data governance, and regulatory oversight, tackling the root causes of environmental harm and social injustice rather than simply fighting their symptoms. Viewed this way, critiques of “techno-fixes” do not negate the engineer’s role but emphasize our responsibility to have a more complete way of thinking about the goals of the systems we build. For example, many engineering approaches ignore the human condition and cognitive factors. We can preserve the optimistic ethos that, through intelligent redesign, humankind can solve even the most entrenched problems—but the key is to combine optimism with careful risk assessment and mitigation of downsides.

Let’s Engineer a better Future

Rather than being overwhelmed by challenges, engineers should see these challenges as unfinished design problems—problems that we have the ability, responsibility, and creativity to solve. The world faces many daunting problems: global warming, pollution, pandemics, antibiotic resistance, food and water scarcity, energy dependency, economic inequality, political instability, cybersecurity threats, urban infrastructure challenges, and the ethical risks of emerging technologies. Each of these is a grand engineering challenge waiting for solutions—through renewable energy systems, medical innovations, AI-driven diagnostics, precision agriculture, smart grids, digital finance platforms, transparent governance systems, enhanced cybersecurity, disaster-resilient infrastructure, and responsible AI frameworks (e.g. this). Engineering has always been about turning uncertainty into progress, and we must continue to rise to the challenge.

The Energy Transition as a Positive Example

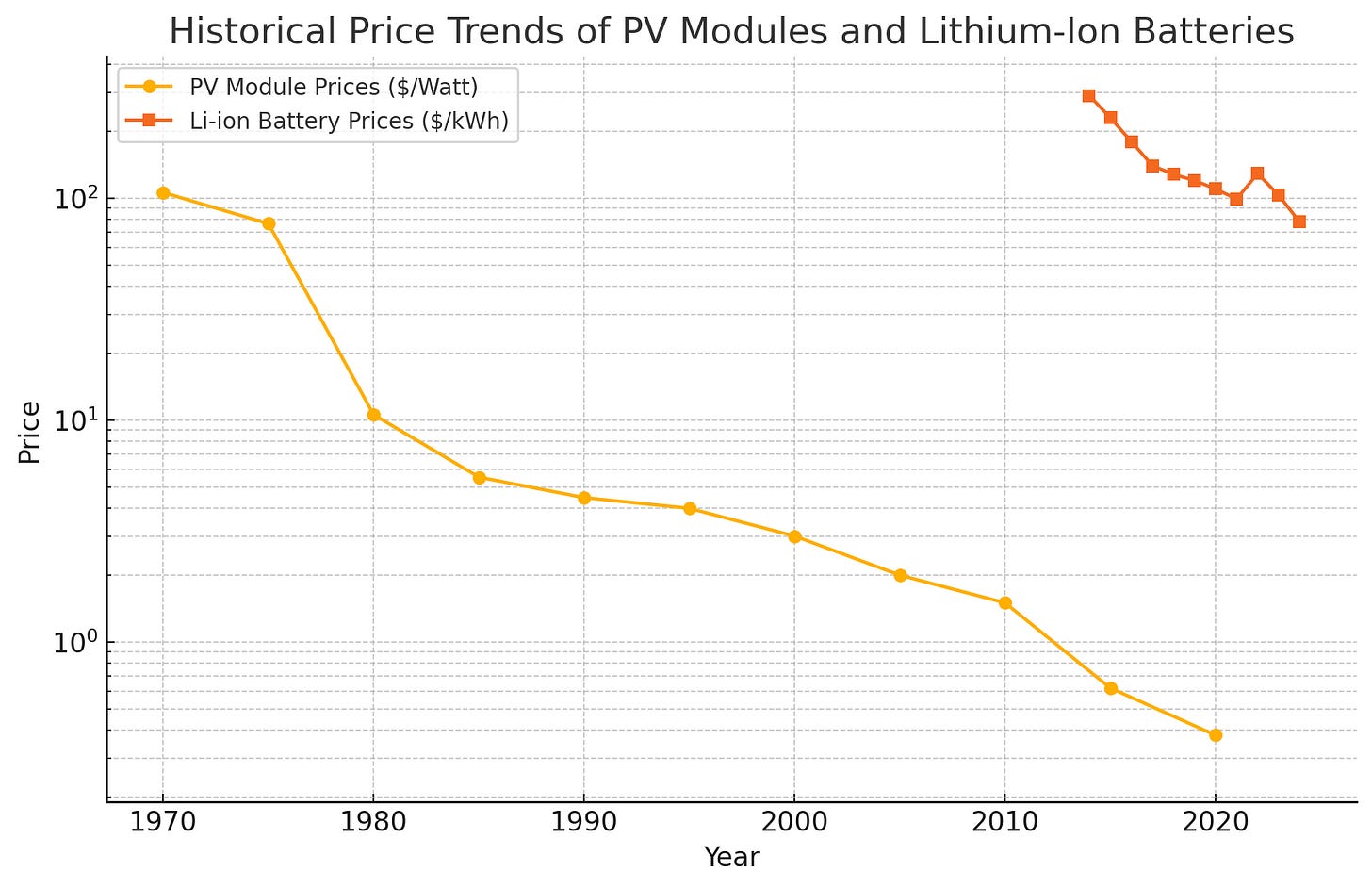

Exponential progress on climate solutions is already visible, most notably in the fast-falling costs of battery storage and solar photovoltaics. Widely circulated graphs from organizations like BloombergNEF and the International Energy Agency illustrate how lithium-ion battery pack prices have plummeted over the last decade, while solar PV costs have followed a similar downward curve. This rapid decrease has spurred global investment in clean energy, creating a feedback loop where greater adoption further drives down costs. By continuing to refine these technologies and scale them worldwide, we can make the transition to renewables both economically viable and environmentally beneficial—showing that we are indeed capable of engineering transformative change at a global level.

A Call to Action for Engineers

I am always inspired by the analogy of real-world decision making with reinforcement learning, where algorithms that are optimistic in the face of uncertainty often dominate. There are many paths; we should explore the ones that could lead to great outcomes instead of settling for paths we already know are less beneficial, even if they are lower-variance. For example, we do not have that much uncertainty about where de-growth would lead us—low uncertainty but low expected value. There are plenty of paths we have yet to explore. Let us do that before deciding to go down roads we already know are no good. Now, let me be clear that I am not arguing for neglecting these problems or avoiding proper risk calculations. We should obviously do that. But we should not go into the future believing that progress is fundamentally negative. Universities are meant to foster the next generation of engineers who will build the future—not just critique it—while teaching humility in the face of complex problems and upholding ambitious goals. If we do not believe in our own ability to create solutions, who will?

My approach builds upon, yet differs from, Andreessen's "The Techno-Optimist Manifesto" (2023). While I share his fundamental belief in technology's transformative potential, I recognize that technological progress without ethical considerations can exacerbate existing inequalities. Unlike Andreessen's more absolutist stance, I argue that critique should inform better engineering—viewing social and environmental concerns not as obstacles to innovation, but as essential design parameters. This middle path acknowledges technology's tremendous potential while remaining mindful of our responsibility to create systems that benefit humanity broadly, not just accelerate progress for its own sake.

I think we should be optimistic about things that will probably turn out well, and pessimistic about things that will probably turn out poorly, and in either case, we should proactively try to make things turn out better than they otherwise would, including via engineering.

Thinking about AI risk is like thinking about how a bridge might collapse. People building bridges do indeed think about how the bridge might collapse. And if they come up with a good answer, then they try to change the design so it won't collapse. And if they can't find any way to do that, then they don't build the bridge at all. Is that "pessimistic"? I dunno. But it’s certainly what bridge-builders have always done, and it’s what they should do!

The problem with Germany's anti-nuclear movement is not that they were opposed to a technology per se, but rather that they were opposed to a technology FOR DUMB REASONS. People also opposed leaded gasoline and CFCs and pouring toxic chemicals into rivers, but in those cases, they were right to do so. If the laser had never been invented, that would have been bad. If fentanyl had never been invented, that would have been good. Etc.

De-growthers tend to be economically illiterate—for example, they often assume that the world is zero sum, and all our nice things are directly plundered from the environment, and therefore if GDP goes up, then evidently we must be plundering the environment that much faster. We should counteract this idea, not because it’s pessimistic per se, but because it’s complete nonsense.

So what does “optimism” mean? If it means “things will probably turn out well”, then you’re advocating that we choose the answer before examining the data, and I suggest that you spend some time on this awesome new website https://www.c4r.io/ 😛 If it means “we should proactively try to make things better than they otherwise would, including via engineering”, then yeah I’m all for it, but that’s a confusing use of the word “optimism”. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯