The fog of war in science is about to lift

There is many problems in science: we are about to see it due to automatic parsing of papers

Science drives progress, and its continued success depends on upholding rigorous research practices. From computers and CAR-T therapies to innovative technologies (and 4X games), science has delivered breakthroughs that shape our world. Yet a closer examination reveals significant methodological issues throughout the literature, highlighting an urgent need for enhanced scientific rigor. Science attracts dedicated researchers, who often give up on exceptional opportunities in industry, who are committed to building a better future through innovation and discovery. However, some researchers may cut corners—either inadvertently, due to gaps in training, or through deliberate shortcuts—which can undermine the integrity of their work. Some estimates (although they may be biased) suggest that up to 10% of research (estimates about other scientists behavior) or .6% “(self professed) involves intentional misconduct and a far larger number involves questionable research practices, underscoring the need for systemic improvements. For us scientists, it is very hard to review for quality and correctness and lack of fraud(although we can automatically do that with images) in any area but the immediate area where we work in. Almost all the problems in the rest of the scientific world, the questionable research practices and fraud, are hidden behind a “fog of war1” - we can not see them2.

Most bad science is not fraud

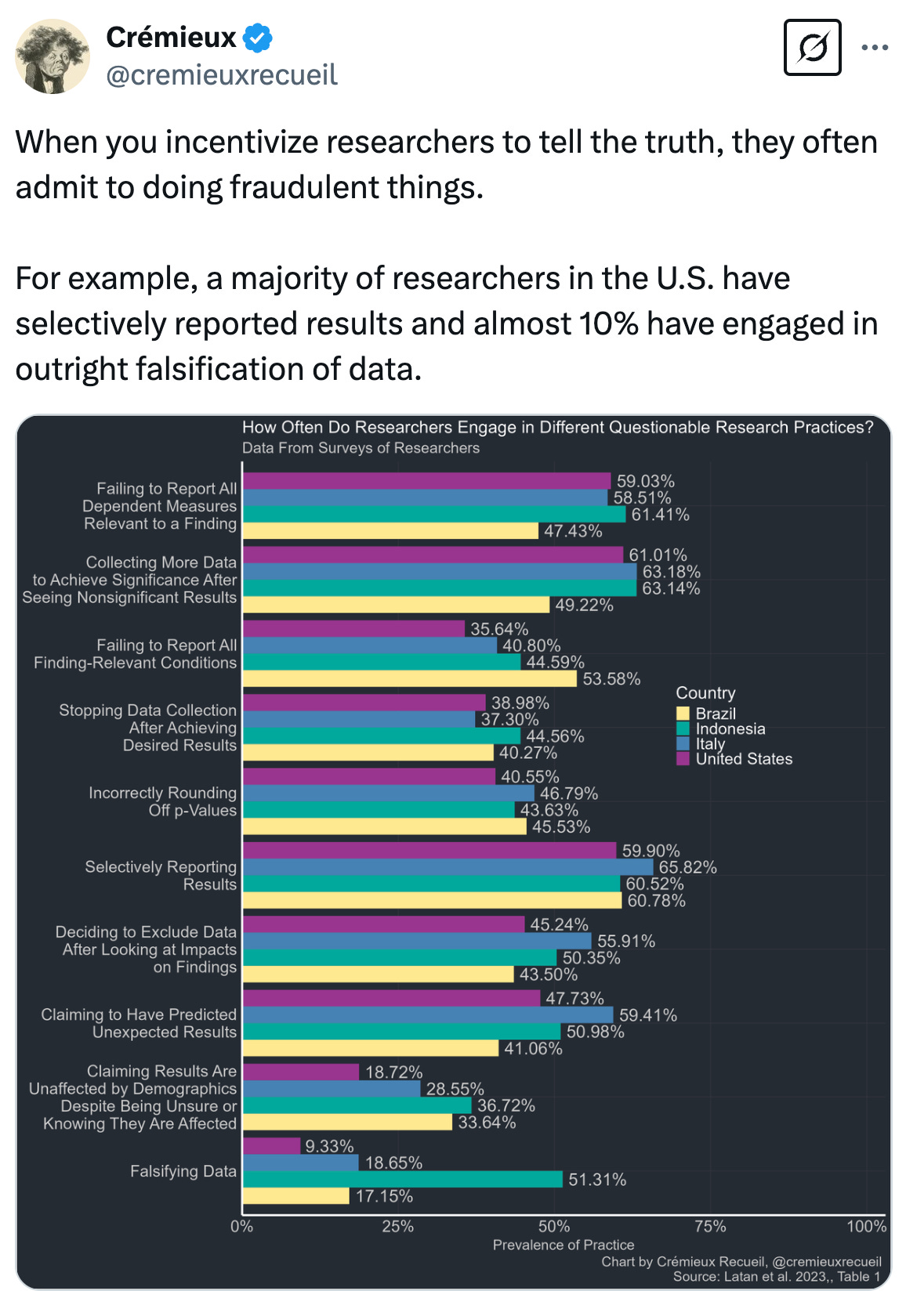

Non-specialists often conflate unintentional methodological errors with outright fraud, which can obscure the critical need for improved training and oversight. Scientists, by and large, do not know that questionable research practices are questionable. Let us look at a list that Cremieux recently put out. It is important to distinguish between deliberate misconduct and inadvertent errors; conflating the two can divert attention from the vital goal of enhancing overall research rigor. We must address intentional misconduct decisively (and yes, I think they should be fired and barred for life) while also investing in better training and resources to help researchers avoid unintentional errors.

A perfectly well-meaning but undertrained scientist may make many of these mistakes or may not understand that their research is based on questionable practices. Universities and the NIH have only recently realized how important it is to teach how to avoid questionable research practices. Let us go through a few of them.

Failing to report (or selectively reporting) all relevant measures or conditions. Some measures sound boring. Are irrelevant to the story the scientist wants to tell. Journal publications overwhelmingly prefer strong, consistent storytelling. And, it feels considerate. Does a meandering story not waste the readers attention? So a lot of scientists report selectively. The fact that this distorts the literature is lost on them.

Collecting more data to get significance and stopping once it significant. A lot of scientists see themselves in the process of showing something that is true. The p-value is just seen as gatekeeping. So how can it be wrong to do this? Well, for example because it makes it likely to find significance even if there is nothing in the data. These effects are hard to understand because for any one scientists they are not observable. It may take decades for someone to redo an experiment. As such, it requires deep statistical intuition, one that us humans are not born with, to get it right.

Excluding data if it makes the analysis be not significant. The scientists view this from the perspective of believing the result. They believe that not excluding the data was a mistake (“its just dirt”). They do not know that this makes it much more likely that they will report (and publish) a finding, even if it is not true.

I would hold that all these questionable research practices are, well, questionable. But they are not done from a perspective of wanting to produce false positives. They are done from a perspective of misunderstanding statistics and believing that if p<0.05 that the effect then is actually real. Regardless of how one gets there. It is this attitude that needs to change. But this is not fraud. This is not even professionally incompetence - we can only be incompetent in the areas where we have any knowledge. Positioning scientists who engage in questionable research practices as fraudulent is missing the most important piece of the story. It is like punishing a hiker for crossing a border that they did not know about. Nonetheless, these behaviors throw a major wrench into the fabric of science (and my main job is an NIH initiative teaching folks to do good science, c4r.io).

But this is rapidly changing. I am starting to get pretty good results when I internally run prompts asking LLMs to review papers for signs of questionable research practices. I have not yet automated it. Probably noone has. But this is getting possible. It is getting possible fast. What that means is that we will soon be able to revisit all papers ever published. We will know where the skeletons are buried.

Why can we not currently review the quality of science (e.g. wrt questionable resarch practices or fraud) at scale?

Why can we not review those far-away branches of science? We can not review them because we only have the prerequisite knowledge in our local area. We can not review them because we do not have enough time. Questionable research practices are often detectable (e.g. it is mightily suspicious if someone ran 131 subjects and got a p value of p=0.0493. It is suspicious if their hypothesis makes no sense based on the literature. It is suspicious if the collection of conditions does not make sense. In other words, if people use questionable research practices they probably leave a trail.

For example, my friend Tim Verstynen was reading a shockingly cool paper that showed that machine learning can near perfectly predict suicidality. If true that would be amazing, we could save people before anything happens. We should invest immediately into this technology to save lives. Only, that this whole paper was apparently the result of questionable practices. Tim and me got the raw data, did a host of forensic data analyses and basically found that many steps of the paper appeared to be questionable. This ultimately led to the retraction of the paper, but not before costing us years to remedy this problem. But such careful forensics is difficult, slow, expensive, and requires experts like Tim, implying that most of the literature will remain behind the “fog of war”.

The fog of war is lifting

But this is rapidly changing. Within at most a year or two, fraud fighters will run LLMs trying to catch every single thing that is going wrong in science. At scale. I am sure that is possible, as I am starting to get pretty good results when I internally run prompts asking LLMs to review papers for signs of questionable research practices. It is clearly getting possible. It is getting possible fast. What that means is that people, scientists or non-scientists, will soon be able to revisit all papers ever published. I am happy for the frauds to be caught (F them). I am worried that a lot of mistakes that people make for a lack of knowing better will be wrongly called fraud (as maybe weakly implied by this). It is better if we start improving our practices right now.

Drawing the right conclusions

A careful analysis will show a surprisingly large proportion of papers have problems. It will show many papers that are basically meaningless. A lot of brilliant scientists will have to admit that much of their older work was problematic. We will find that much of the newer work is better. We will also find that there is a significant amount of fraud and these folks will fight tooth and nail against us accepting the results. And yet, despite all the problems that science has had over the years, we still have lots of papers making big progress in relevant areas. The key is to reform science. The key is to fund the good research that is solid. And with this comes a call for the scientific community: As methodological shortcomings become increasingly apparent (and soon through automated methods), we must reform our research practices immediately. By committing to rigorous science, we not only safeguard our credibility but also ensure that our discoveries continue to improve lives.

A lot of 4X games have a mechanism where much of the map is not visible to the player. That’s where other players are. This makes games more interesting as it preserves a notion of surprise. The downside is that it is hard to plan, it is expensive to learn.

I want to briefly comment on a critique of this post that I understand but that I do not agree with. People say we should circle the wagons. While some believe that staying silent might protect us from external criticism, I contend that openly acknowledging and improving our shortcomings is the surest way to build public trust. Our goal must be to produce research that is both innovative and rigorously validated, ensuring that our work continues to merit support and drive progress.

I'm confused. Why should scientists care what Elon Musk's favorite anonymous race scientist thinks about anything? Is the way forward in science appeasing anonymous Twitter shitposters?