What I built, what shifted my priors, and why I'm optimistic

What I built, what shifted my priors, and why I'm optimistic

It is January 2026. I am on a plane back to the US after a European vacation, and I am doing the only year-end review I trust: not “what did I publish,” but “what did I make more reliable.” Applied to 2025, that filter points to infrastructure. Tools that reduce avoidable failure in projects, better ways to train scientists for the job they actually do, and a few concrete steps toward making biological and machine intelligence easier to understand. And we are moving so fast! That is the through-line below: what I built, what shifted my priors, and what now feels more possible than it did a year ago. It is an exciting time. I do not know what the next year will bring; neither for me nor for the field.

Field building

1) PlanYourScience.com: less rushing, better science

In May I announced PlanYourScience, motivated by a familiar pattern: we do preventable damage to our own projects because we do not plan. The app turns a big checklist of common project failure modes into a workflow people can actually use, without it feeling punitive. The key premise is simple: AI should not think for us. It should make us think. About 10,000 people have used it so far, enough to convince me it is useful.

2) Neuro4Pros: leadership training for young computational neuroscience faculty

One of the most satisfying things I helped build in 2025 was Neuro4Pros, a week-long retreat for early-career faculty in systems and computational neuroscience. The goal was pragmatic: rigor, mentoring, lab management, and a setting that makes it easier to learn those skills as humans. The design reflects an opinionated stance on training: a small cohort (about 30), highly participatory learning, and a curriculum that treats mentorship, wellbeing, and management as core scientific skills, not side quests.

Some big neuro ideas

Object-based Attention (NeuroAI)

Object-based attention as a recurrent control loop. In the recurrent-gating model, the core commitment is architectural and causal: recurrent connections implement a multi-stage internal gating process. Bottom-up pathways carry features, while top-down and lateral pathways carry attentional gating signals. The model is built to do things brains seem to do: recognize and segment stimuli, and it can be prompted with object labels, attributes, or locations, and account for a set of behavioral and neural signatures that many attention modules do not try to explain, including object binding, visual search, inhibition of return, and relatively late attentional onset. It is aiming to be a mechanism, not just a pattern matcher.

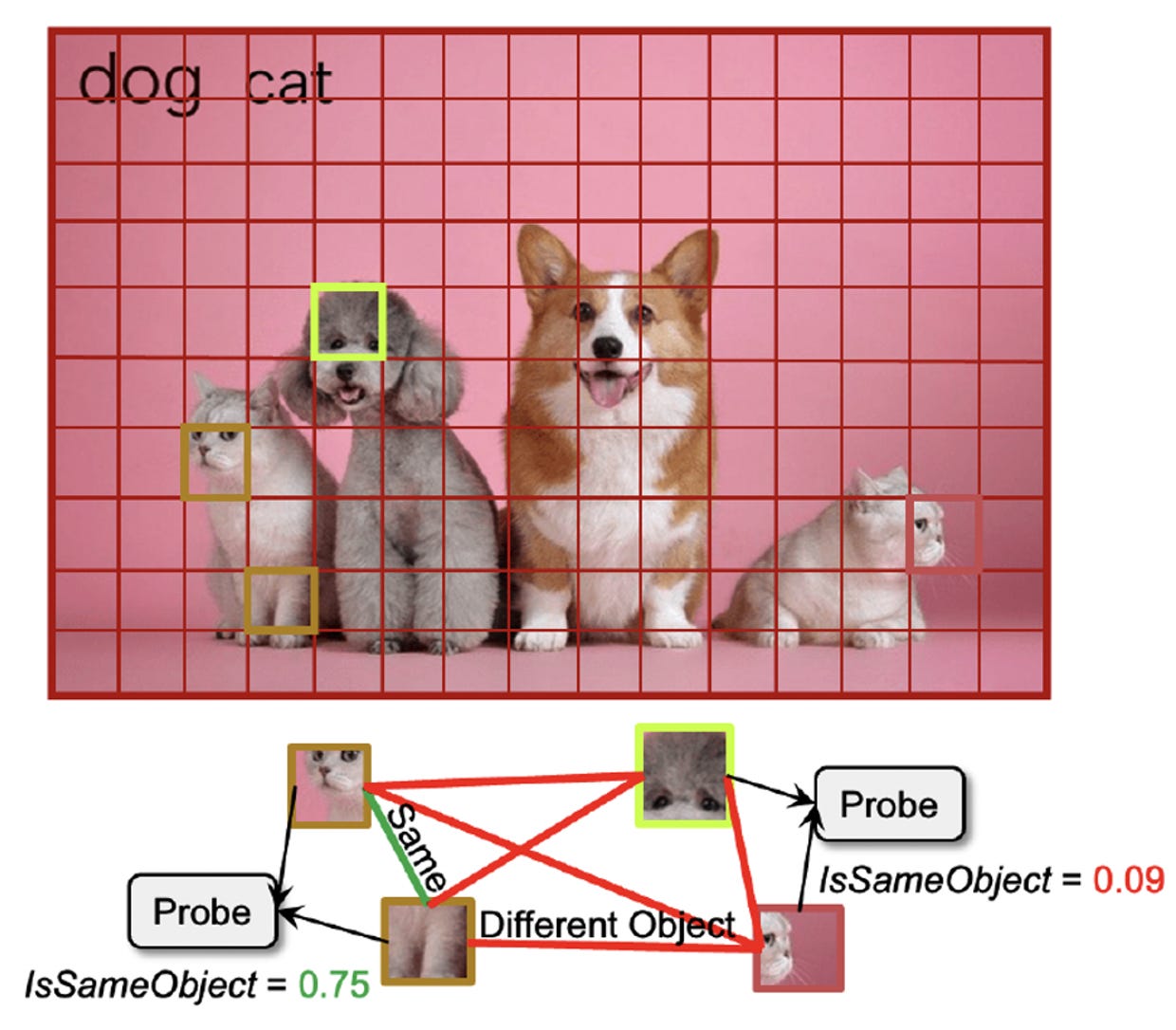

In ViTs, binding can emerge from scale and objective. Yihao’s NeurIPS 2025 paper is an annoying result for anyone who wants to say “you need recurrence for binding.” She defined an explicit binding predicate, IsSameObject (whether two patches belong to the same object), and decoded it from patch embeddings in large pretrained vision transformers at over 90% accuracy. The effect is strong in self-supervised ViTs (DINO, MAE, CLIP) and much weaker in ImageNet-supervised ones, suggesting it is learned from the training objective rather than being a trivial architectural artifact. They also report that ablating the binding signal hurts segmentation and pushes against the pretraining loss. ViTs bind because that is useful.

Why this contrast matters (and why it makes me optimistic). Together these results separate two narratives. The recurrent-gating model offers a mechanistic story about what carries what, why attention has dynamics, and why “late onset” and “inhibition of return” might be features rather than bugs. The ViT result offers a scaling and objective story: binding can emerge because it is useful for prediction, and training objectives can induce and compress it into a usable representation. My takeaway is not “one is right.” It is that we now have a clean, testable distinction. If transformers can learn a binding subspace, the interesting question becomes what the brain gets from making attention an explicit recurrent control loop. My bet is that the divergence shows up where brains live: limited data, active sensing, rapid retasking, and cases where the “right” object is defined by goals rather than by the statistics of the training set.

Simulating nervous systems

The phrase “simulating nervous systems” used to trigger eye-rolls because it sounded grand and vague. In 2025, it felt more like an engineering roadmap with increasingly nontrivial milestones.

A key shift is when simulations start predicting biology, not just running big graphs. A good prototype is the Turaga (Janelia) line of work: start with a connectome, add a hypothesis about what the circuit is trying to compute, then fit unknown single-neuron and synapse dynamics with modern machine learning. In the fly visual system, the resulting connectome-constrained model predicts responses across many neuron types to visual input and it matches a large body of prior experimental results.

A related approach is showing up in smaller nervous systems, like connectome-constrained latent variable models for C. elegans: use a biophysical simulation as a generative prior, use whole-brain calcium imaging to pin down missing parameters, then test whether connectome constraints improve prediction of withheld neuron activity. They do, and the modeling clarifies which synapse assumptions buy predictive power.

And the Seung contribution is a big part of why this is now a program rather than a vibe. FlyWire-scale reconstructions, and the connectomics ecosystem around them, are turning “wiring diagram” from static artifact into substrate you can compile into models that make quantitative, testable claims about function.

That is not “we simulated a nervous system” in the full biological sense. But it is a meaningful shift: executable connectomes plus inferred dynamics are starting to produce predictions you can use like a scientific instrument, not a demo.

I also kept pushing on the longer-term goal of whole-nervous-system simulation. It is obviously one of the things we need to try. It still feels like something we need to attempt soon, and I remain surprised by how hard it is to fund.

And a big idea about econ and AI

I also wrote a working paper with Ioana Marinescu on what happens when “intelligence” scales at computer-science speeds but the rest of the economy does not. Economists often model AI as just another form of capital, while some AI narratives implicitly treat intelligence as the whole bottleneck and predict singularity-like growth. Our move is to separate the economy into an intelligence sector and a physical sector, and then ask how substitutable they really are.

If intelligence and physical inputs are complements (our default assumption), then you get intelligence saturation: once intelligence is high enough, physical throughput becomes the bottleneck, and the marginal returns to still more intelligence go to (almost) zero. That has a concrete labor implication: because AI prices fall much faster than those of physical capital, intelligence tasks automate first, pushing people toward the physical sector. Wages can follow a hump-shaped path (up, then down) depending on parameters, especially how substitutable physical and intelligence outputs are (play with it here).

For neuro/AI intuition: think “better brains” paired with fixed effectors - a C. elegans worm with infinite intelligence would still be pretty much be limited by sensors, effectors, and the fact that it can be killed trivially by pretty much any human with just a bit of bleach. It’s the physics of the niche.

What I think were some interesting 2025 papers in systems neuroscience

There were too many awesome papers. But here are just some that I thought were interesting during this flight.

1) Recording scale keeps climbing, especially in primates

A very practical frontier in systems neuroscience is: can we record large populations, across many regions, in animals that do cognition in the way we care about. In 2025, a Nature Neuroscience paper reported large-scale, high-density brain-wide neural recording in nonhuman primates, with probe designs intended to access deeper and broader targets in primate brains.

2) Connectomics is turning into a substrate for prediction, not only description: structure to function

The connectome story in 2025 felt less like “look at this wiring diagram” and more like “can we use structure and function together to build models that generalize.” But clearly, in my discussion with people in the field the upcoming transition is to translate from microscopy images to function (see this by Holler et al).

3) The power of knowing the weights

The paper asks how much the connectome actually constrains a brain’s dynamics.

It argues that wiring alone often leaves many possible dynamical regimes consistent with the same connectivity, so “simulate from the connectome” is underdetermined.

But once you add recordings from a relatively small subset of neurons, that ambiguity collapses fast. In their framework, a connectome plus a few well-chosen recordings can be enough to predict the activity of unrecorded neurons surprisingly well. The practical implication is optimistic: you may not need exhaustive measurements to build useful circuit simulations.

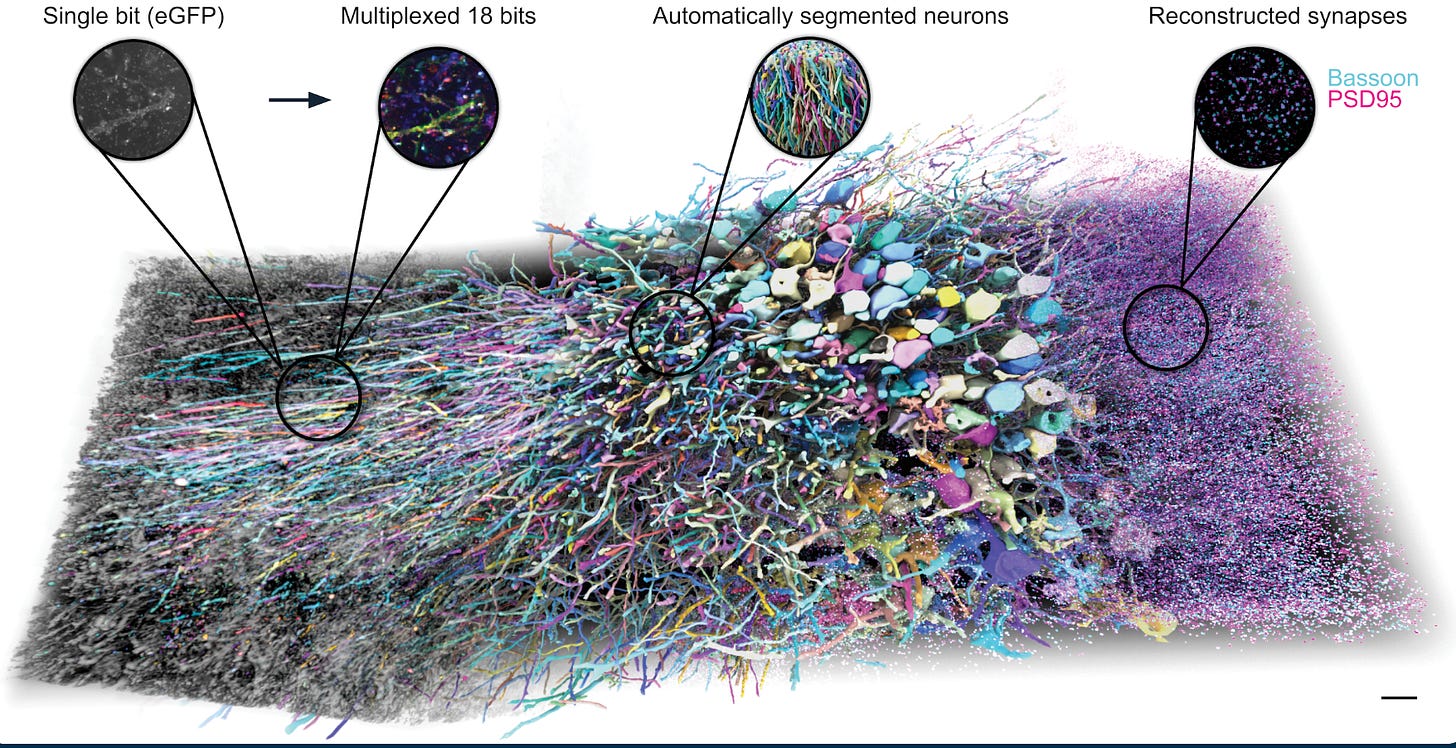

4) Impressive optical connectomics

Also, E11 Bio (CEO Andrew Payne) presented PRISM, a expansion-light-microscopy-based workflows that appears significantly cheaper than EM long-term and should replace EM imho. On top of expansion, they give each neuron and its processes an identity via combinatorial protein barcodes, which dramatically reduces the ambiguity that normally makes tracing brittle. n a mouse hippocampus demonstration, they show that the barcodes enable a kind of automated self-correction, helping reconnect fragmented arbors and reduce split and merge errors, leading to much higher-quality reconstructions with less manual proofreading. Very cool is that they can scale to many molecules detected, a major enabler for structure to function.

Now the plane is descending, and that same filter still feels like the right one. The most satisfying parts of 2025 were not “outputs” in the narrow sense, they were small increases in reliability: better connectomics, fewer ways for projects to self-sabotage, more explicit training in leadership and mentorship, and models that struggle with what we mean by “mechanism” . If 2026 goes well it will bring even more focus. More science that is easier to do well, easier to learn, and harder to fool ourselves with.

I am also surprised that it is so hard to fund whole nervous simulation efforts. However, in 2025 I was interested to see that several groups were able to create start-ups in the brain simulation space, like Eon Systems, Netholabs, and Memazing. So maybe what you need to do is start a company! =)

Planning your science projects in advance sounds really helpful. Would have prevented a LOT of mistakes from myself and a few other labmates if we had somewhat of a roadmap instead of learning by trial-and-error.